A Concert of African Diaspora Composers, from the 18th Century to contemporary Puerto Rico

For this year’s award-winning Black Composers Concert, curator Artina McCain taps composers of African descent from Europe, Central and South America, the Caribbean, and the United States.

By Dana Wen, February 1, 2019

Last year, the Boyd Vance Theatre at the George Washington Carver Museum was so packed that ushers had to cart in extra chairs. The crowd, a sea of diverse faces, included parents with small children in tow, chit-chatting grandmas, and young couples. All of them had braved the cold winter day to hear some chamber music, specifically a program featuring Black female composers.

Every February, the Austin Chamber Music Center’s Black Composers Concert provides a midwinter musical treat after the blizzard of the holidays. Curated by pianist Artina McCain, the annual chamber music concert celebrates the contributions of Black composers from around the world. Now in its 16th year, the annual tradition was a bit of a local secret until recently.

“We’ve been standing room only for the last three or four years,” says McCain recently, still sounding a little surprised at the project’s runaway popularity.

But after listening to last year’s carefully-crafted program, it’s easy to see why the crowds keep coming. Each Black Composers Concert focuses on a central theme, providing a common thread to draw the audience in. This helps McCain expertly guide her listeners through a program of music that may be unfamiliar or completely new to them.

Clearly, it’s a journey of learning and musical discovery that audiences find thrilling. Along with the full auditorium, last year’s concert, titled “The Black Female Composer”, garnered McCain a 2018 Austin Critics Table Award for Best Classical Instrumentalist.

This year, McCain has set her sights on a global scale. “The African Diaspora”, the 2019 Black Composers Concert (performances on February 9 and 10), features composers of African descent from Europe, Central and South America, the Caribbean, and the United States. The global focus ties in with “Landscapes”, the theme of Austin Chamber Music Center’s current concert season, which explores ideas of heritage and homeland around the world.

Since previous Black Composers Concert programs focused primarily on the African-American experience, McCain relished the opportunity to represent an even-wider range of musical viewpoints in “The African Diaspora”.

“There are so many composers of African descent all over the world, and their music isn’t programmed that often,” she laments. “That led me on this journey of learning about all these composers that lived in different parts of the world. This has been a really interesting and fun program (to curate) because the pieces are so different from each other, but all of the composers were classical or formally trained.”

As a young piano student with traditional conservatory training, McCain noticed that Black composers were often left out of history classes and concert programs. She took it upon herself to learn more, uncovering a treasure trove of rarely-performed repertoire. What began as a sense of curiosity led to a lifelong passion, resulting in a doctoral thesis (on African-American composer George Walker) and eventually her current role as curator of the Black Composers Concert – the ideal platform for exploration and sharing.

“I had played so many Black art songs and Black spirituals, which more people are probably familiar with,” explains McCain. “But I wanted to learn more about the concert repertoire, more about Black composers’ contributions to Western music.” Often, these are the stories that don’t make it into the history textbooks and symphony halls.

A prime example of this is George Walker, whose Sonata for Cello and Piano is featured on the “The African Diaspora” program, performed by McCain and cellist Elizabeth Lee.

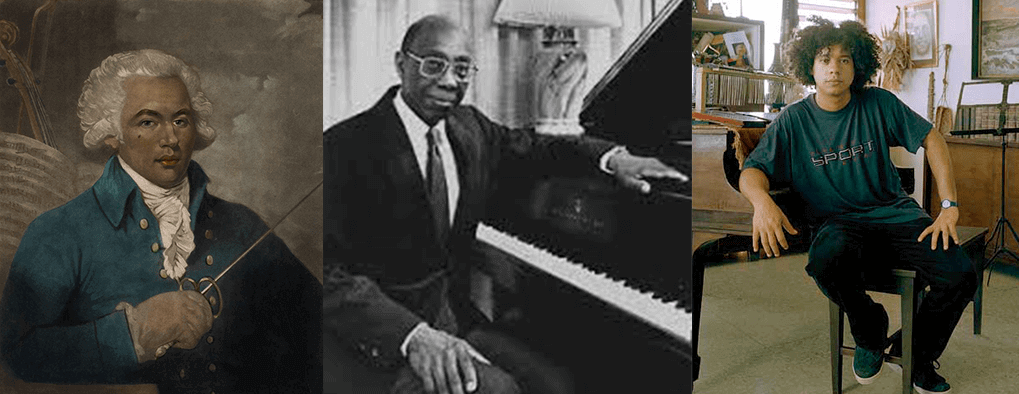

A talented pianist, Walker graduated from Oberlin Conservatory and Curtis Institute of Music in the 1930s and 1940s, at a time when opportunities for Black classical musicians in the U.S. were slim. Despite this, he built a distinguished career as a performer, teacher, and prolific composer, producing works for piano, chamber ensemble, and orchestra. Though Walker’s music draws primarily from his training as a classical pianist, it includes elements of jazz, gospel hymns, and other uniquely American musical forms.

In his later years, Walker began to gain wider recognition for his contributions, winning the 1996 Pulitzer Prize in Music. He was the first Black composer to receive the award. By the time of his death in 2018, Walker’s music had gained popularity, though he remains far from a household name.

McCain would like to change that. “I wanted to pay homage to George Walker because he is, in my opinion, one of the great American composers,” she says resolutely. “I believe he probably doesn’t have the same status as George Gershwin or Aaron Copland because Blacks were not celebrated in that way in the 1940s, 50s, and 60s. A lot of Black musicians have always known and respected his music, but I find as far as mainstream classical performers and (ensembles) go, many people don’t know his works or don’t program them.”

Another 20th century composer featured on the “The African Diaspora” program is violinist Noel DaCosta. Born in Nigeria in 1929, DaCosta spent his youth in Jamaica and eventually moved to New York City, where he established his musical career.

Like Walker, DaCosta drew upon jazz rhythms and harmonies when writing his compositions. For “The African Diaspora”, McCain chose the blues-influenced “Walk Around ‘Brudder Bones’,” a thrilling and demanding work for unaccompanied violin, featuring soloist Christabel Lin.

Along with presenting music from a variety of countries and cultures, McCain also chose works to represent different periods in Western music history. It’s a way to underscore that Black composers have been prolific, if not widely recognized, throughout the centuries.

Joseph Bologne (typically known by his noble title, Chevalier de Saint-Georges) was one of the earliest known classical composers of African descent. A movement from his Sonata No. 2 for Violin and Piano will be performed by McCain and Lin.

Born in 1745 in Guadeloupe, a French colony in the Caribbean, Saint-Georges was the son of a wealthy French landowner and an African slave. He spent much of his youth in Paris, where he received a noble’s education and developed a reputation as a master fencer. Eventually, the young Saint-Georges turned to music, becoming a prolific composer and conductor (while still finding time for swordsmanship activities and military campaigns).

As a curator, McCain rarely misses the opportunity to present something new. One highlight of “The African Diaspora” is a medley of Puerto Rican bomba y plena tunes performed by local percussionist Samuel López and members of his ensemble.

A signature feature of Puerto Rico’s musical landscape, bomba y plena encompasses a series of rhythmic patterns that trace their ancestry back to African tribal music. Throughout the past 400 years, bomba y plena has been used to evoke the Puerto Rican experience, from slavery and political protest to occasions of celebration and dance.

“We’ve never had a percussionist on the program, so that’s going to be a great surprise,” explains McCain excitedly. “I really wanted to include music from Puerto Rico (in the program). Sammy’s an amazing musician, so I just step back and let him do what he does best. I will be listening to the music for the first time at the concert, along with the audience.”

Along with her role as curator for the Black Composers Concert, McCain juggles a busy schedule as a professor, lecturer, and touring artist. Though many of her performances feature “mainstream” favorites from the classical repertoire, McCain is pleased that her work with the Black Composers Concert has generated interest and demand for lesser-known music by composers of color. In 2019, she will present several “encore” performances of last year’s “The Black Female Composer” program alongside baritone James Rodriguez.

An album of solo piano music is also in the works. Titled “Heritage: An American Legacy”, the collection draws inspiration from McCain’s work with Black composers and her love of American music.

And she’s already looking ahead to the 2020 Black Composers Concert, hoping to shine light on living composers who are still actively contributing to the musical fabric of the 21st century.

Through all of this, McCain cites a desire for equality as her driving factor.

“I want to see people of different shades, hues, ethnicities, and (genders) on the stage performing equally on every program and in every orchestra. That would be a dream.”